Take a good look at the photo above. Does anything seem unusual about the house on the right, 23 Leinster Gardens, compared to the one on the left, number 22?

Take a good look at the photo above. Does anything seem unusual about the house on the right, 23 Leinster Gardens, compared to the one on the left, number 22?

Something definitely looks a bit odd about the windows in number 23:

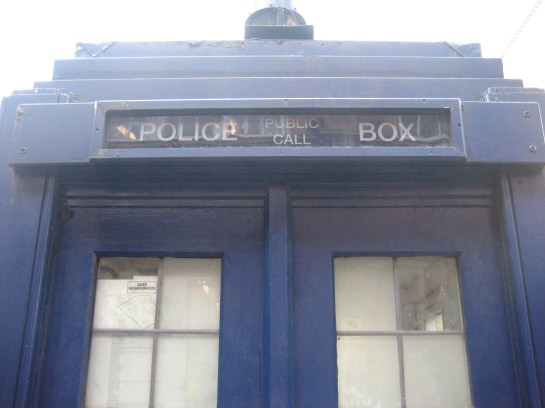

And the front door appears a bit suspect as well:

And the front door appears a bit suspect as well:

This isn’t like the door of 10 Downing Street, which can only be opened from the inside.

This isn’t like the door of 10 Downing Street, which can only be opened from the inside.

This is a door through which, to paraphrase Flanders and Swann, no-one departs and no-one arrives. For this door belongs to a house that does not exist.

Like Dolly Parton, Blackpool and extreme political organisations of both left and right, it is all front. And the reason is the London Underground – or, as it would have been pronounced when this elaborate facade was constructed, London’s Under-Ground.

The trains that first ran along the railway line that passes below Leinster Gardens were steam-powered. The locomotives needed somewhere to vent the fumes that built up inside the engines. But where to do this, in a neighbourhood jostling with upmarket residences for whom a large gap in the ground would appear both unsightly and undignified?

The answer, as with most tricks of the eye, can be found round the back:

Number 23 Leinster Gardens, and also its neighbour number 24, were erected as frontispieces, not houses.

Number 23 Leinster Gardens, and also its neighbour number 24, were erected as frontispieces, not houses.

Behind them, what once were steam-driven trains on the Metropolitan Railway, and which are now Circle and District line services, rumble directly below what otherwise would be dining rooms, pantries and sculleries:

It’s a typically British compromise between the aspirational and the functional. What’s out of sight to the residents of and visitors to the expensive flats and hotels on Leinster Gardens can also be put out of mind, unless you happen to glance out of a back window. Which, back in the 1860s, nobody of “sound” upbringing would ever have thought of doing.

It’s a typically British compromise between the aspirational and the functional. What’s out of sight to the residents of and visitors to the expensive flats and hotels on Leinster Gardens can also be put out of mind, unless you happen to glance out of a back window. Which, back in the 1860s, nobody of “sound” upbringing would ever have thought of doing.

Meanwhile the exposed tracks are hidden from ground level by a brick wall. Only the mildly curious, and the obsessive chronicler, would think to peek above it.

Mind the gap: