A part of me likes the idea of living directly above an Underground station. There’s a cafe in Liverpool that I used to always enjoy visiting, in which you could sometimes feel the rumble of Merseyrail trains passing underneath. When I first saw the film Seven, I was mildly jealous of Mr and Mrs Brad Pitt getting to live in a flat that shook evocatively thanks to a nearby mass transit system. And how many times I’ve eyed those flats in Chiltern Court astride Baker Street station, envious of the residents, all of whom are naturally pursuing a lifestyle that is part Kenneth Williams, part John Betjeman.

A part of me likes the idea of living directly above an Underground station. There’s a cafe in Liverpool that I used to always enjoy visiting, in which you could sometimes feel the rumble of Merseyrail trains passing underneath. When I first saw the film Seven, I was mildly jealous of Mr and Mrs Brad Pitt getting to live in a flat that shook evocatively thanks to a nearby mass transit system. And how many times I’ve eyed those flats in Chiltern Court astride Baker Street station, envious of the residents, all of whom are naturally pursuing a lifestyle that is part Kenneth Williams, part John Betjeman.

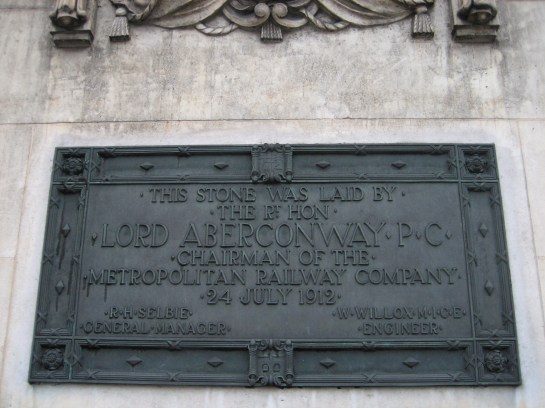

A different part of me knows all of this is fantasy and that living directly above the Underground is possibly the path to physical and emotional wreckage. But a third part of me (yes, I have many) wonders if the reality is somewhere in between, and that a place like Chiltern Court has to be lived in before it can be truly loved or loathed. It is the most elaborate of what are best described as the “trimmings” of Baker Street, all of which date from the remodelling of 1911-13, conceived to turn the place into a brand-encrusted hulk of the Metropolitan line, where getting on a train was but one of the riches on offer.

Chiltern Court might be beyond the reach (and budget) of most of us, but other more modest, less swaggering trimmings are not. Like the MR insignia embroided within the grilles over the porthole windows, and the WH Smiths & Son sign above what is now a ticket office. The tiles were given a sympathetic scrub-up in 1985, the same time the old platforms were so touchingly restored. The sign must have appeared something of a charming curio in the mid-80s, when WH Smiths was at the peak of its pocket money-absorbing powers. Nowadays, with the chain such an aesthetic calamity, the lettering is both enchanting and deeply depressing.

Chiltern Court might be beyond the reach (and budget) of most of us, but other more modest, less swaggering trimmings are not. Like the MR insignia embroided within the grilles over the porthole windows, and the WH Smiths & Son sign above what is now a ticket office. The tiles were given a sympathetic scrub-up in 1985, the same time the old platforms were so touchingly restored. The sign must have appeared something of a charming curio in the mid-80s, when WH Smiths was at the peak of its pocket money-absorbing powers. Nowadays, with the chain such an aesthetic calamity, the lettering is both enchanting and deeply depressing.

There’s a “Luncheon and Tearoom” sign that’s equally wistful, leading not to the tantalising prospect of a London Underground-manufactured hot beverage, the tea leaves allowed to drip through roundel-shaped strainers, but instead to absolutely nowhere at all. The entrance is bricked in, and now houses automatic ticket machines. Meanwhile biscuit-coloured arches and panels in the ceiling, timber handrails, iron balustrades and over-the-top 1912 timestamps add to this bran tub of post-Edwardian-era fancies:

I vowed to myself I would get through this entry without any reference to Sherlock Holmes, and it looks like I might have made it. The trimmings that adorn Baker Street share with their gastronomical namesake an ability to enhance something that is already of substance. We might not make it into the sumptuous kitchenettes of Chiltern Court, let alone dine in the long-vanished restaurant visited by Betjeman in 1972. But to push this desperate simile even further, these are trimmings that linger on the palate and even, if you’re in the mood, bring a lump to the throat. Alimentary, you might say.

I vowed to myself I would get through this entry without any reference to Sherlock Holmes, and it looks like I might have made it. The trimmings that adorn Baker Street share with their gastronomical namesake an ability to enhance something that is already of substance. We might not make it into the sumptuous kitchenettes of Chiltern Court, let alone dine in the long-vanished restaurant visited by Betjeman in 1972. But to push this desperate simile even further, these are trimmings that linger on the palate and even, if you’re in the mood, bring a lump to the throat. Alimentary, you might say.