I’ve been a bit sniffy on this blog about the Underground stations designed by Leslie Green.

I’ve been a bit sniffy on this blog about the Underground stations designed by Leslie Green.

They’re the ones with the dark red exteriors made up of hundreds of glazed terracotta blocks. There are dozens of them around the city, and you’re bound to encounter a few of them on even the most fleeting of visits to London. Which is precisely why I have a bit of a problem with Green. To sum up what I’ve discussed before, if you’ve seen one of them, you don’t really need to bother with any others. The differences are superficial rather than significant, prompted by expediency rather than imagination.

Sometimes, however, a variety of riches can be found inside one of Green’s otherwise character-less creations.

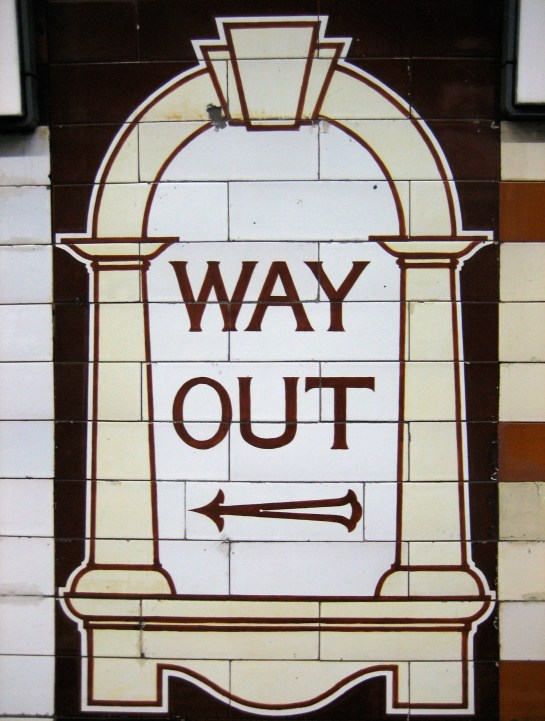

Holloway Road has a good collection of his signature work for the interior of an Underground station. Both platforms were given a long-overdue refurbishment in the late noughties, which certainly benefited the tiling. Green’s trademark ‘Way Out’ and ‘No Exit’ designs for the walls of the platforms look in a pretty good state, considering they were first put up in 1906:

But for once, a Leslie Green station is more than the sum of its predictable, rudimentary parts.

But for once, a Leslie Green station is more than the sum of its predictable, rudimentary parts.

As well as those familiar mock signs (based on his design for the ticket windows in the booking hall), Green sprinkles Holloway Road with a bit of glamour: more Cricklewood than Hollywood, as Ernie Wise would say, but still rather beguiling.

There are very swish ‘To The Trains’ signs in the little passageways between the adjacent platforms:

And there’s a much larger treat in the shape of the track-side wall of both platforms, which have been left completely free of advertising.

And there’s a much larger treat in the shape of the track-side wall of both platforms, which have been left completely free of advertising.

The effect is to highlight, dramatically and memorably, more of that instantly elegant original signage:

I’m not sure how many other places on the Underground can boast such a sparse, yet also so attractive a contrast. I know the effect is much the greater thanks to the majority of stations having these walls absolutely covered with adverts. But even taken by itself this is bold and, certainly for Green, unexpected.

I’m not sure how many other places on the Underground can boast such a sparse, yet also so attractive a contrast. I know the effect is much the greater thanks to the majority of stations having these walls absolutely covered with adverts. But even taken by itself this is bold and, certainly for Green, unexpected.

Perhaps I’ve been a little too hard on the old bugalugs. Not a lot, mind. Just a little.