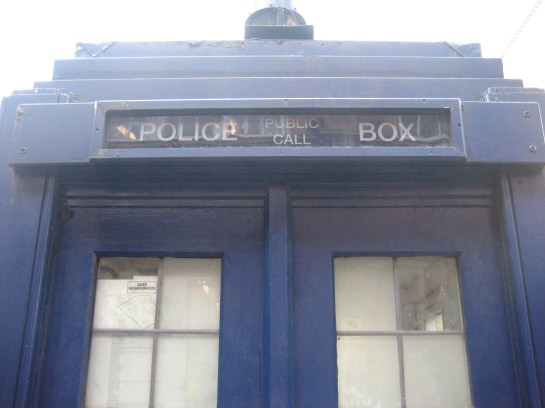

Parked by the eastern entrance to Earl’s Court is something that competes for attention from passers-by with a frozen-yoghurt parlour, a branch of Pret a Manger, and a kiosk selling international newspapers.

Parked by the eastern entrance to Earl’s Court is something that competes for attention from passers-by with a frozen-yoghurt parlour, a branch of Pret a Manger, and a kiosk selling international newspapers.

When I was there, it was losing to all three.

Like the TV series, it’s a relatively contemporary reimagining of a once ubiquitous staple of everyday life that had ended up somewhat irrelevant and unloved.

Unlike the TV series, it’s seen better days, looks somewhat shabby and could do with sprucing up a bit. The dirt has, however, led to some topical graffiti:

You can’t use it to call the police. You can’t even go inside. And those that have the power to do so better not think of lighting up.

You can’t use it to call the police. You can’t even go inside. And those that have the power to do so better not think of lighting up.

It’s probably sterner on the outside than the inside.

It’s probably sterner on the outside than the inside.

A thoughtfully-embossed brass panel fixed to the box explains who, where and when:

I’m used to being eyed suspiciously while taking photographs outside an Underground station. On this occasion, though, not only did I fail to be eyed at all, I also got the sense of being actively ignored, even shunned. It was as if the twin bodies of the London Underground and Doctor Who had suddenly aligned in such a fashion as to send anybody in close orbit scurrying for less obsessional climes:

I’m used to being eyed suspiciously while taking photographs outside an Underground station. On this occasion, though, not only did I fail to be eyed at all, I also got the sense of being actively ignored, even shunned. It was as if the twin bodies of the London Underground and Doctor Who had suddenly aligned in such a fashion as to send anybody in close orbit scurrying for less obsessional climes:

Earl’s Court station: change here for the District, Circle, Piccadilly and Gallifrey lines.

Earl’s Court station: change here for the District, Circle, Piccadilly and Gallifrey lines.